It's always something, isn't it? No matter where you live in the world, death seems to be lurking around nearly every corner -- if not at someone else's hand, something else. If a suicide bomber or a gun-wielding maniac doesn't get you, maybe the weather, the unsteady earth, your own body, or your own government will. This idea really hit home last year when I visited the Killing Fields in Cambodia. How could a country that now seems like one of the most peaceful places on earth have hosted such a massive active public graveyard just a few decades ago?

I know nothing about the gun laws in Cambodia today -- guns weren't even the Khmer Rouge's execution weapon of choice -- but I do know this: Where there's a will to kill, there's always a way. In the words of Mr. Beach, my high-school earth-science teacher, "Sometimes I feel like a bug on the sidewalk waiting to be squashed."

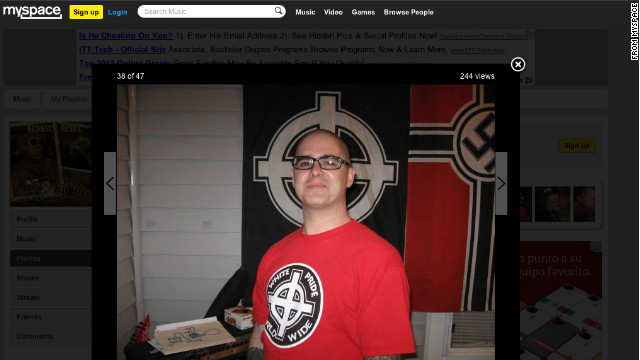

When he said that, I couldn't quite relate -- not yet. I was too young. I didn't pay that much attention to the news, so I didn't realize how unsafe my own country could be. There's no question about that now. Just 16 days after a lunatic armed with a gun opened fire at a sold-out July 20 midnight premiere of The Dark Night Rises in Aurora, Colorado, killing 12 and wounding dozens more, another madman did the same at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, this time killing six and wounding four. James Holmes, the first gunman, was apparently crazy, the second, Wade Michael Page, a Neo-Nazi white supremacist, was overflowing with hate. Crazy and hate: Close neighbors on the street leading to mass murder.

As I read about the second U.S. killing field, I didn't know what to think or write or say. For once, I was speechless.

I wish I'd been at such a loss for words, or at least used fewer of them, two weeks ago when an English friend and I were debating Americans and guns. I should have simply agreed that the guns have got to go and left it alone, but I interpreted the way my friend expressed his point of view (the implication, to my sensitive ears, being "You crazy, violent Americans and your stupid guns") as just another roundabout way to bash us, the U.S., so I fired back. It's not like the U.S. has a lock on lunacy. Make guns readily available to people anywhere, and see how they behave. How can the actions of a deranged few represent the American way?

I stand by my assertion that it's not about the American psyche. I've never owned a gun, held or fired one, and as far as I know, neither has any American whom I consider to be a close friend. It's not fair to judge Americans in general based on the actions of a few of them (not that my friend was actually doing that, but some people do, especially when they begin a sentence with "Americans...") -- no more so than it would be to cock an eyebrow at every black person on the street every time one person of color commits a high-profile crime. Or assuming that every guy wearing a turban is a terrorist. It's thinking like this that led to the massacre in that Sikh temple.

We don't make -- or necessarily support -- the laws that we have to follow. And just because laws were made hundreds of years ago doesn't mean that we have to follow them today. Yes, the Bill of Rights grants U.S. citizens "the right to bear arms," but the U.S. is a different place now than it was in 1791, when the Bill of Rights was ratified and applied only to white men (a shining light on the collective American psyche at the time). One of the biggest similarities between now and then, though, is the level of lawlessness that prevails because of the number of handguns owned and operated by private individuals.

It would be so easy to pin the blame on Hollywood filmmakers who glorify violence onscreen, but that would be too easy. Movies don't kill people (at least not off-screen), guns do. Yes, Holmes identified himself as the Joker when he was apprehended by police, and he was clearly influenced by the opening scene in the previous Batman film, 2008's The Dark Knight. But it wasn't the onscreen antics of the late Heath Ledger (who won an Oscar for playing the Joker in The Dark Knight) that killed a dozen people that night. It was Holmes's mini-arsenal of guns.

I'm not sure how to get rid of them all at this point, or if that's even possible. Outlawing and confiscating them will probably be more successful at getting them out of the hands of law-abiding citizens. The type of person who would go into a holy space and open fire or enter a schoolyard and start shooting would most likely still manage to acquire firearms illegally. That said, although there would be a lot of holes to plug and twists to negotiate, it shouldn't stop us from trying.

Lobbying for stricter gun-control laws is a good political strategy, but it's no longer a practical one. How many lives would they save? Not those of the victims of Holmes, an honors student, Ph.D. candidate and reportedly all-around law-abiding citizen who purchased four guns at local stores legally and 6,000 rounds of ammunition legally on the Internet. (I can't even fathom that you can purchase such things on the Internet, where it's impossible to know for sure to whom anything is being sold.)

Stricter gun-control laws wouldn't necessarily have kept someone like Holmes from obtaining his firearms. A rigid pre-purchase psychiatric evaluation may have, but I'm not ready to entrust my life to loopholes in doctor-patient confidentiality. Only prohibiting guns from being privately bought and owned would would have protected those moviegoers from Holmes's one-man firing squad. If confiscating guns and banning the sale of firearms and ammunition to the general public saves just a handful of lives, wouldn't it be worth it? Isn't every single life a precious gift? Think of it as nuclear disarmament on a different scale.

For as long as I can remember, I was a staunch supporter of stricter gun-control laws, or no guns at all (military and police personnel excepted -- I wholeheartedly believe in our right to bear arms through them), until I was attacked and robbed in my apartment in Buenos Aires in 2007. It's strange how an incident like that can change a person. For a while there, I was hungry for vigilante justice, even if it was only vicariously through fictional characters. When I saw someone on TV or in the movies turn the tables on an attacker, I cheered. I probably liked The Brave One a lot more than I would have had I not understood exactly how Jodie Foster's character felt.

For a while after the robbery, I considered buying a gun for protection. But eventually, I realized that if I had owned a gun when my apartment was burglarized, or if it had happened to me in the U.S., where burglars are more likely to be armed because, well, the law gives them every right to be, I probably wouldn't be alive today. If I'd had a gun, the robbers likely would have found it and used it on me when I came home mid-home invasion. In the end, I installed an alarm system instead.

I'll probably never feel 100 percent safe in my own home again. And I haven't felt safe in public places since September 11. It's a cross I have to bear, my own personal burden. But I'd rather live with it than run around packing heat, or go on reading about public massacres in the U.S. every few weeks. Enough! (It's still my country, and it always will be, regardless of where I live.)

Phasing out guns might not make going to the movies completely safe, but isn't the violence we see onscreen unnerving enough? Are we so dead set on protecting our so-called right to bear arms that we're willing to die for it, too?

No comments:

Post a Comment